Inflammation and heart disease: A smoldering threat

Cardiology experts call for more widespread testing for inflammation, which is just as important as cholesterol in causing clogged heart arteries.

- Reviewed by Paul M. Ridker, MD, Contributor

The evidence linking inflammation to heart disease is "compelling and clinically actionable," according to a 2025 scientific statement from the American College of Cardiology (ACC). But what is inflammation, exactly? How does it affect your heart, and what actions should you take to address this often-silent hazard?

"Over the past 30 years, research has shown that inflammation is as important as cholesterol in the development of atherosclerosis," says Harvard Medical School professor Dr. Paul Ridker, a co-author of the statement. "The time has come for universal screening for inflammation, which is easily measured with an inexpensive blood test that's been available for more than 20 years," he says.

Inflammation: Friend and foe

Inflammation comes in two forms: acute (which is short-lived and often causes symptoms such as pain) or chronic (which is long-lasting and often silent). Acute inflammation is your body's natural immune response to a health threat such as an injury or infection - an outpouring of white blood cells and chemical messengers that help heal wounds or eliminate pathogens. With chronic, low-level inflammation, the spark that ignites the process comes from other harmful substances such as high blood sugar or excess fat tissue. This slow, insidious process has become increasingly common in our current environment (see "Inflammation: A modern problem with ancient roots") and is a key factor in many health conditions - including cardiovascular disease.

Even if you have only a small accumulation of cholesterol inside your heart's arteries, your immune system treats that plaque like any other invader. Although the resulting immune attack covers the plaque with a fibrous cap, the smoldering inflammation underneath can cause the cap to rupture. The contents then mingle with blood, forming a clot that could block blood flow. These clots are responsible for most heart attacks and strokes.

Inflammation: A modern problem with ancient rootsMost of our early ancestors perished from one of three things: infection, injury, or starvation. The few that survived may have had genetic variations that helped protect them from those threats. "All of us who are alive today are favored with those variations - otherwise, we wouldn't be here," says Dr. Paul Ridker, director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women's Hospital. A pumped-up immune system could help fend off infections like malaria, cholera, and tuberculosis. Better blood clotting may have allowed women to survive the complications of childbirth. An ability to keep blood sugar levels elevated may have helped people endure starvation. "It's actually a beautiful story of evolutionary biology in action," Dr. Ridker says. But once you've survived long enough to reproduce, those genes are less of an advantage. In our modern world, where there's an abundance of food and little need to move around, our genetic legacy has become a liability. All those things that protected us in the past - abundant immune cells, clotting factors, and plenty of blood sugar circulating through our bodies - cause inflammation. "These adverse consequences of evolutionary survival are a major part of why we now have an epidemic of diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease," says Dr. Ridker. |

The missing link?

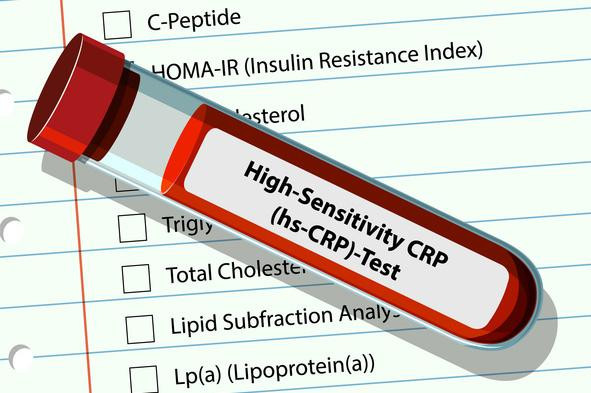

Almost half of all heart attacks and strokes happen in people who have none of the four modifiable risk factors for heart disease: smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes, says Dr. Ridker. Inflammation has long been suspected as a possible culprit. Now, there's clear evidence that links elevated markers of inflammation to heart disease - and shows that in certain situations treating inflammation can prevent future heart attacks and related problems, he adds. That's why the ACC statement calls for universal screening with a high-sensitivity test for C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of inflammation. Most insurers cover this inexpensive blood test, called an hsCRP test. An hsCRP result lower than 1 milligram per liter (mg/L) means you are at lower risk; 1 to 3 mg/L indicates average risk; and 3 mg/L and up means you are at higher risk for cardiovascular disease, heart attack, and stroke.

"We should be testing people for CRP along with cholesterol in their 30s and 40s so we can intervene earlier in life," says Dr. Ridker. Checking CRP is especially important among women, for whom cardiovascular disease remains underdiagnosed and undertreated, he adds. Also, people with autoimmune disorders should monitor CRP, since their immune systems are already in overdrive.

The good news is that lifestyle changes (see "How to reduce inflammation in the body") can help, as can statin drugs, which lower cholesterol. Anyone with a persistently high hsCRP result should consider asking their doctor about taking a statin (or, if they're already taking one, switching to a higher dose), regardless of their LDL level, according to the statement.

What if you have heart disease and you're already taking a high-intensity statin? If your hsCRP result is higher than 2 mg/L, ask your doctor if you're a good candidate for low-dose colchicine (0.5 mg daily), the first FDA-approved anti-inflammatory therapy proven to reduce heart disease risk when added to statin therapy.

How to reduce inflammation in the bodyThe same habits that lower your risk of heart disease and other chronic conditions can help reduce inflammation:

|

Image: © blueringmedia/Getty Images

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Paul M. Ridker, MD, Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.