What is a bubble study?

Ask the doctor

Q.

After my wife’s recent minor stroke, her cardiologist scheduled her for a “bubble study.” What are they looking for, and what should she expect during the test?

Q.

After my wife’s recent minor stroke, her cardiologist scheduled her for a “bubble study.” What are they looking for, and what should she expect during the test?

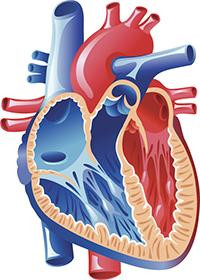

A. Also called a saline contrast study, a bubble study is performed during an echocardiogram (heart ultrasound) to reveal more information about blood flow through the heart. Doctors often recommend bubble studies for people who experience an unexpected stroke — that is, those who have no obvious stroke risk factors such as high blood pressure or atrial fibrillation. The results can provide clues about a major risk factor for the stroke, and may affect recommendations for treatment.

During your wife’s bubble study, she’ll receive an injection of a solution that contains harmless bubbles of air into a vein in her arm. This fluid will circulate through her bloodstream to the right side of her heart. On the live ultrasound video, the bubbles will be visible as they travel into the heart’s upper chamber (right atrium). Normally, the bubbles move down to the lower chamber (right ventricle) and then out through the pulmonary artery into the lungs, where they are filtered out of the blood.

But in some people, bubbles are seen traveling through a tiny, flaplike tunnel between the right and left atria. This opening is present in all fetuses as a normal part of development and usually closes up within a few weeks after birth. But in about 25% of people, the hole fails to close fully and is known as a patent foramen ovale (PFO).

For the most part this condition is harmless, and most people with a PFO don’t know they have one. However, PFOs may contribute to certain rare strokes, which are thought to happen when a blood clot travels through the hole from the right atria to the left atria. Because the clot bypasses the lungs (which trap tiny clots before blood recirculates through the body), it can travel to the brain, lodge in a blood vessel, and cause a stroke.

Your wife may also receive a transcranial Doppler study in conjunction with the bubble study. This specialized ultrasound of the brain’s vessels can show if the bubbles injected into the vein are moving all the way up to the brain. When that’s the case, the risk of stroke related to a PFO may be especially high.

PFOs could contribute to some cryptogenic strokes (those with no clear cause), especially in people ages 60 and younger. For these people, if testing shows a PFO, doctors sometimes recommend a procedure to close the opening, especially if it is large. But for most people, clot-preventing drugs are the initial treatment.

Image: © rabbitteam/Getty Images

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.