The case for watching your blood sugar

Being mindful of glucose levels isn't just for people with diabetes. Here's what influences your blood sugar — and why you should care.

- Reviewed by Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

Among the social media trends catching dietitian Nancy Oliveira’s eye is people wearing continuous glucose monitors, small devices that track blood sugar (glucose) levels 24 hours a day. But these folks don’t have diabetes; they just want insight into how their eating and exercise patterns affect blood sugar fluctuations.

Oliveira, manager of the Nutrition and Wellness Service at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital, has also noticed some of her female patients with prediabetes are sporting the skin sensors, which are readily available and relatively inexpensive. The devices have conventionally been used by people with diabetes, but they no longer require a prescription.

The upshot? Monitoring blood sugar may be useful for some people even if they don't have diabetes — and being mindful of glucose levels can help virtually everyone move through the day more smoothly, helping battle issues such as fatigue, cravings, and mood swings.

“I can understand why people without prediabetes or diabetes want to check their blood sugar, because Americans have more unhealthy habits than healthy ones,” she says. “Even though genes play a role in developing prediabetes or diabetes, it can still develop solely from unhealthy lifestyle habits — eating choices, stress, skimping on sleep and exercise — that can all affect how our bodies process sugar.”

Blood sugar basics

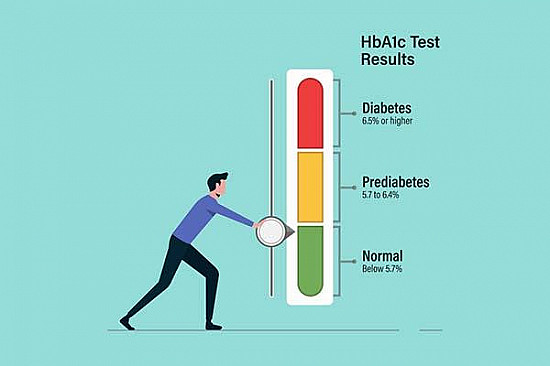

Prediabetes — which means blood sugar levels are higher than normal but not high enough to be diagnosed as type 2 diabetes — is on the rise, affecting more than one in three American adults and about half of those 65 and older, Oliveira says. It’s a stealthy condition that doesn’t typically produce warning signs.

While obesity plays a large role in developing it, a slice of people diagnosed with prediabetes are quite healthy, Oliveira says. “Stress, being too sedentary, not sleeping well — those are other things that lead to blood sugar not being processed optimally,” she says.

Menopause can be a particularly likely time to develop prediabetes, because diminished estrogen and progesterone levels promote fat storage in the belly. “The location of that fat is associated with insulin resistance,” Oliveira explains. “We’re making insulin, but our bodies don’t use it as efficiently.”

Meanwhile, diabetes rates continue to rise as well, significantly increasing over the past 25 years, according to the CDC. Nearly 12% of people in the United States have diabetes, as do more than 29% of people 65 and older. The American Diabetes Association recommends all adults 35 and older, regardless of risk factors, be screened at least once every three years for prediabetes and diabetes. This typically involves a simple blood test.

Blood sugar variables

If you’re otherwise healthy, you don’t need to formally monitor your blood sugar beyond periodic screenings with your doctor, Oliveira says. But staying attentive of blood sugar levels on a broader basis can help you with a range of healthful goals, from avoiding the “afternoon slump” to curbing cravings, boosting mood, and managing your weight.

To reap these benefits, it helps to understand how our bodies react to various foods. When we eat carbohydrate-heavy meals, for example, blood sugar spikes — and then nosedives again a short time later, leaving us feeling drained. But by eating balanced meals and snacks that include protein, fat, and carbohydrates, we maintain more stable blood sugar levels, keeping energy levels consistent.

Blood sugar levels aren’t just a function of what we eat, however. Chronic stress or sleep deprivation can also drive them up, Oliveira says. “People always look at food as the only reason blood sugar goes up, but it might not be food,” she says. And haphazard meals and snack times can also lead to topsy-turvy blood sugar levels.

“The best way to handle the cravings and mood swings is to have a narrow range of blood sugar, where it never gets too high or too low,” Oliveira says. “If it goes too low, and you overeat later because you’re too hungry, it can then swing too high, which can impair your mood.”

“You could then have a 'crash,’ making you feel tired,” she adds. Too much variation “can also affect your weight by altering your metabolism.”

Striving for balance

Oliveira suggests these strategies to keep blood sugar levels stable:

Time your meals. Eating at regular intervals — ideally every three hours — should prevent extreme blood sugar fluctuations. “If you’re not eating for five hours during the day, and then you suddenly eat a lot, that will likely cause your blood sugar variation to be wider,” she says.

Practice portion control. Sensible serving sizes along with regular mealtimes are the “two things that are your best bet for having more consistent blood sugar in a narrower range,” Oliveira says.

Prioritize healthy foods. Oliveira advocates a Mediterranean-style diet rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, seafood, and skinless poultry. These foods will keep you fuller longer and minimize blood sugar swings, which are more likely to occur after you eat ultra-processed foods.

Stay active. Aim for 30 minutes or more of moderate or vigorous exercise at least five days a week. “Like meals, it’s better when exercise is spaced consistently,” she says. “Exercise makes your body better able to use the insulin you make.”

Avoid smoking. Smoking can indirectly affect blood sugar by increasing insulin resistance and encouraging other unhealthy habits, such as poor food choices.

Keep a log. Either on paper or an app, track what you eat and when. “When people start logging, they’re almost always a little surprised by the amount or types of food they’re actually having,” she says.

Can a common diabetes drug promote longevity?People with diabetes are living longer these days than in past decades, before the widespread use of a drug called metformin. Dr. JoAnn Manson, chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital, explored whether there’s a connection. A recent study Dr. Manson co-authored suggests there may be. Published in July 2025 in the Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, it showed that older women with diabetes who used met for min—a first-line diabetes treatment—were far less likely to die before age 90 than peers with diabetes who used an older class of diabetes medication called sulfonylureas. “We were interested in looking at whether there were any advantages of being on metformin versus other medications for diabetes in terms of living beyond age 90, which is the definition we used for exceptional longevity,” says Dr. Manson, who is also a professor of women’s health at Harvard Medical School. “It was surprising there was a substantial, 30% lower risk of dying prior to age 90.” Researchers evaluated data from the Women’s Health Initiative, a large, national study that tracked nearly 162,000 participants ages 50 to 79 for more than 30 years. This analysis focused on 438 women 60 and older who were newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and hadn’t used any diabetes medications before starting treatment. Half were taking metformin and half, a sulfonylurea. The researchers also took into account participants’ age, lifestyle habits, how long they’d had diabetes, other health conditions (such as high blood pressure, heart disease, lung disease, or cancer), body weight, and any other medications they were taking. The study was observational, meaning it did not randomly assign treatment and could not prove that taking metformin lengthened life, only that an association exists. The disparity in results between the two drugs could be chalked up to several factors, Dr. Manson says. Evidence suggests metformin increases insulin sensitivity and lowers the level of a growth factor implicated in cancer risk. “There’s also some evidence metformin may decrease inflammation and slow something called cellular senescence, where cells stop dividing and replicating,” she says. Dr. Manson can envision a future where even people without diabetes might take metformin because of its potential effects on longevity—with a caveat. “If it’s shown to have a benefit in extending life span, it likely would be prescribed to slow biological aging,” she says. “We’re not yet to that point—we still need large-scale clinical trials.” “The take-home message is that metformin looks like a promising but still unproven approach to extending healthy longevity,” she adds. “I recommend anyone with diabetes discuss with their doctors the pros and cons of the different medications that are available.” |

Image: © DGM007/Getty Images

About the Author

Maureen Salamon, Executive Editor, Harvard Women's Health Watch

About the Reviewer

Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.