Is tight blood sugar control right for older adults with diabetes?

- Reviewed by Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

It's well known that uncontrolled diabetes leads to damage to the major organs of the body, such as the heart, kidneys, eyes, nerves, blood vessels, and brain. So, it is important to ask how tightly blood glucose (also called blood sugar) should be controlled to decrease the risk of harm to these organs.

Blood sugar: too high, too low, or just right?

To answer this question, first let's discuss how diabetes is different than other chronic health conditions. For example, a doctor can tell you that your cholesterol levels need to be below a certain number to lower the risk of heart disease. Diabetes is different. Diabetes is a unique condition in which both high and low glucose levels are harmful to the body.

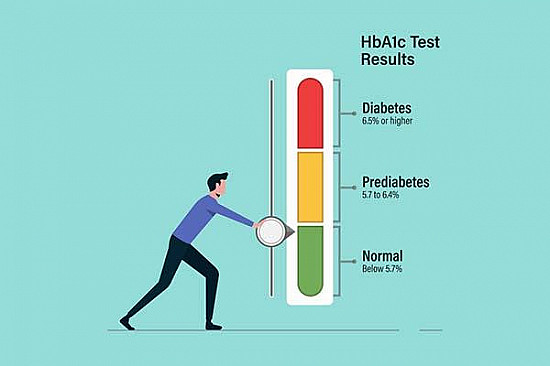

Diabetes control is measured as A1c, which reflects average blood sugar levels over the past two to three months. High glucose levels (A1c levels greater than 7% or 7.5%) over a long period can cause damage to the major organs of the body. However, medications and insulin that are used to lower glucose levels can overshoot and lead to glucose levels that are too low. Low glucose levels (known as hypoglycemia) can result in symptoms such as rapid heartbeat, excessive sweating, feeling dizzy, difficulty thinking, falling, or even passing out.

So, both high and low glucose levels are harmful. Thus, diabetes management requires balancing the risk of high and low glucose levels, and requires constant assessment to see which of these glucose levels is more likely to harm an individual patient.

Different blood sugar goals over a lifetime

The next consideration in answering the question about tight glucose control is to understand why younger and older adults need different goals. In younger individuals, longer life expectancy means a higher risk of developing complications over many decades of life. Younger adults typically recover from hypoglycemic episodes without severe consequences.

On the other hand, people in their 80s or 90s may not have several decades of life expectancy, and so the concern about developing long-term complications due to high glucose levels is decreased. However, hypoglycemia in these individuals may lead to immediate consequences such as falls, fractures, loss of independence, and subsequently a decline in quality of life.

In addition, tighter control of diabetes frequently requires complicated treatment regimens, such as multiple insulin injections at different times of the day or a variety of glucose lowering pills. This further increases the risk of hypoglycemia, as well as stress, to both older patients and their caregivers at home.

Identifying the why of blood sugar control

Thus, when considering goals for blood glucose in older adults, it is important to ask why we are managing diabetes. As the reason to tightly control diabetes is to prevent complications in the future, tighter control of diabetes could be a goal in older adults who are in good health and have few risk factors for hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia risk factors include previous history of severe hypoglycemia that required hospital or emergency department visits, memory problems, physical frailty, vision problems, and severe medical conditions such as heart, lung, or kidney diseases.

In older individuals with multiple risk factors for hypoglycemia, the goal should not be tight control. Instead, the goal should be the best control that can be achieved without putting the individual at risk for hypoglycemia.

Lastly, it is important to remember that health status is not always stable as we get older, and the need or ability to keep tight glucose control may change over time in older adults. Goals for all chronic disease, not just blood sugar control, need to be individualized to adapt to the changing circumstances associated with aging.

Adapted from a Harvard Health Blog post by Medha Munshi, MD

About the Author

Harvard Health Publishing Staff

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.