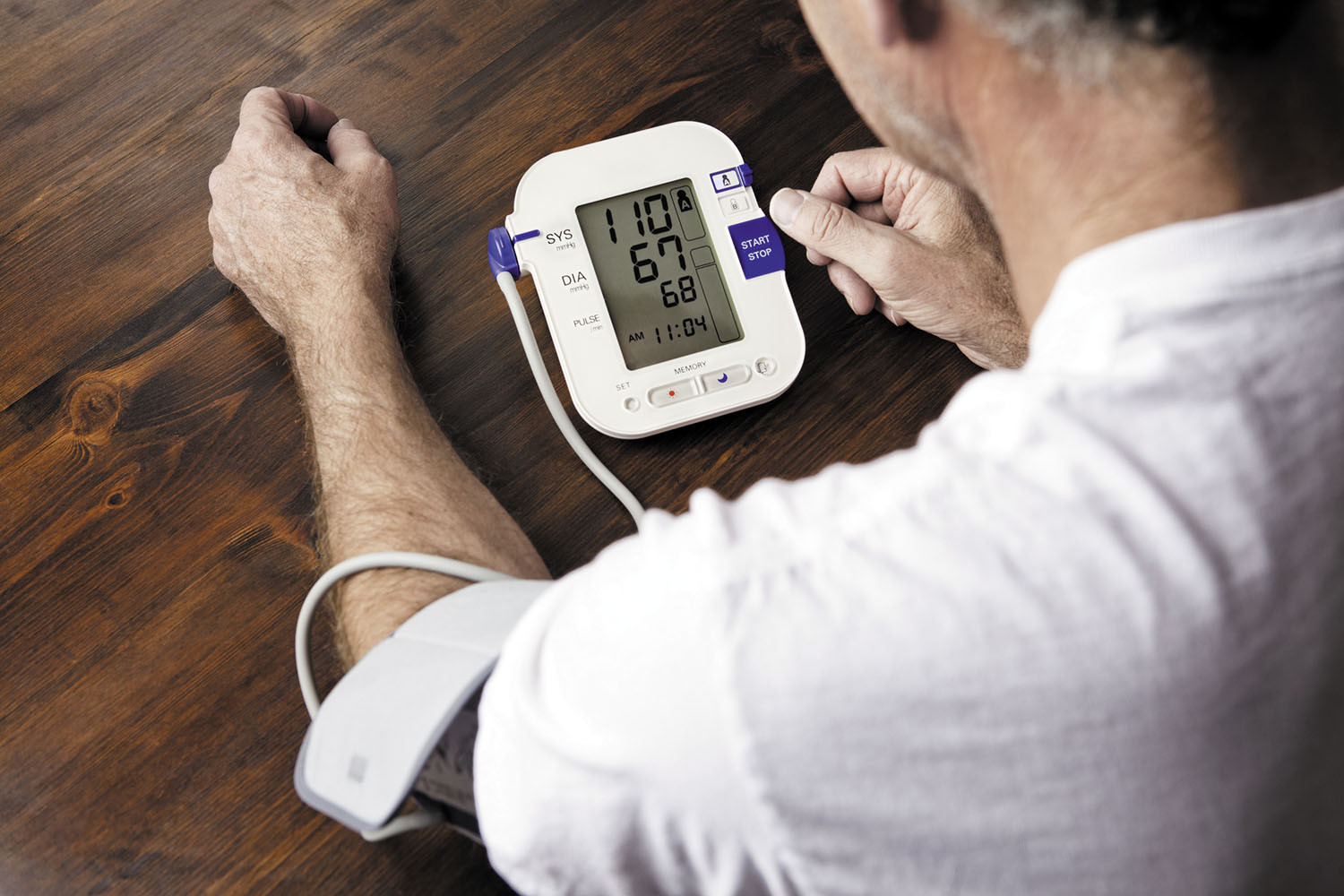

A look at diastolic blood pressure

Aggressively lowering high systolic blood pressure (the top number) can reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke. But how significant is the diastolic (bottom) number?

When it comes to managing blood pressure, doctors tend to focus on lowering the top (systolic) number, and for good reason.

"It’s been well established that aggressively treating high systolic pressure can help lower one’s risk for a heart attack or stroke," says Dr. Stephen Juraschek, a blood pressure specialist at the Hypertension Center of Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

But what about the bottom (diastolic) number? It also plays an essential role in heart health, although it tends to get overlooked.

Tale of two numbers

The two blood pressure numbers measure the heart at work and rest. Systolic pressure is the pressure in the arteries when the heart contracts to pump blood throughout the body. The higher the number, the harder the heart works to pump blood.

Diastolic pressure is the pressure during the resting phase between heartbeats. "This pressure plays a critical role in helping coronary vessels supply oxygen to the heart muscle," says Dr. Juraschek.

According to current guidelines, normal blood pressure is a systolic number less than 120 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) and a diastolic number less than 80 mm Hg. A systolic number of 120 to 129, with the diastolic measurement less than 80, is deemed "elevated."

When it comes to diagnosing high blood pressure (hypertension), either number can be an indicator if persistently elevated. For instance, you’re said to have Stage 1 hypertension if your systolic pressure is 130 to 139 or your diastolic pressure is 80 to 89 — or both. Stage 2 hypertension is defined as either (or both) 140 or higher for systolic or 90 or higher for diastolic.

"It’s important to keep track of both numbers because in many cases, if the systolic is high, so is the diastolic," says Dr. Juraschek.

Exceptions to the rules

However, there are exceptions. While systolic pressure tends to increase with age as blood vessels weaken and narrow, diastolic pressure declines after age 50.

Why? Arteries become less elastic with age. If they become too stiff, arteries that expand with the systolic push of blood have a harder time springing back between heartbeats, which causes diastolic blood pressure to drop.

Another possible cause of declining diastolic pressure is endothelial dysfunction, a condition where the coronary arteries on the heart’s surface constrict instead of opening.

It also is possible to have only a high systolic number, a condition known as isolated systolic hypertension. This is a common type of high blood pressure among older adults. Isolated systolic hypertension happens because less elastic arteries have trouble accommodating surges of blood. Blood flowing at high pressure through these arteries can damage their inner lining, accelerating the buildup of cholesterol-laden plaque. This further stiffens and narrows the arteries, which elevates systolic blood pressure while diastolic pressure remains within a normal range.

Lower but not too low

Is diastolic pressure ever a serious concern? While lower is better for overall blood pressure, you don’t want either number to drop too low. A very low systolic blood pressure increases the likelihood for weakness, lightheadedness, and fainting.

Surprisingly, a too-low diastolic number may signal a higher risk of heart issues, according to a study published Feb. 1, 2021, in JAMA Network Open. This study included people with high cardiovascular risk who received medication to lower their systolic blood pressure.

The researchers found that among those with systolic blood pressure less than 130, a diastolic blood pressure of less than 60 mm Hg was linked to more heart attacks and strokes. However, those with diastolic values between 70 and 80 mm Hg had the lowest risk of heart disease.

For most older adults, the goal should be to keep the systolic blood pressure close to 120 mm Hg, and perhaps a bit lower, as long as the diastolic pressure stays at 60 mm Hg or higher.

Lifestyle changes like reducing dietary sodium, increasing potassium, exercising more, and maintaining a healthy weight are always the cornerstones of treatment, even if you also need medication.

The less common problem is a high diastolic pressure with a normal or slightly elevated top number. The treatment approach here is similar, with lifestyle changes first and blood pressure-lowering drugs when necessary.

Image: © cglade/Getty Images

About the Author

Matthew Solan, Former Executive Editor, Harvard Men's Health Watch

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.