Fibroids: Not just a young woman's problem

These uterine growths can crop up even as menopause looms and beyond.

- Reviewed by Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

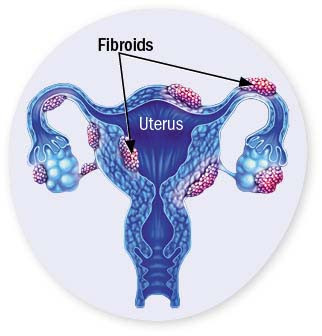

For many women, the approach of menopause is cause for celebration. After decades of monthly bleeding, periods will finally be a thing of the past, as will pregnancy worries. But some of us eagerly anticipate the transition for another reason: waning estrogen levels often improve fibroids, noncancerous growths in the uterine wall that affect up to eight in 10 of us by age 50.

For many women, the approach of menopause is cause for celebration. After decades of monthly bleeding, periods will finally be a thing of the past, as will pregnancy worries. But some of us eagerly anticipate the transition for another reason: waning estrogen levels often improve fibroids, noncancerous growths in the uterine wall that affect up to eight in 10 of us by age 50.

Women in their 40s or early 50s whose fibroids cause only mild problems may be told to be patient, since fibroids rely on estrogen to thrive. But for those with more distressing signs — including heavy bleeding, pelvic or lower back pain, bloating, frequent urination, or painful sex — there's a chance menopause won't bring relief. Stealthy growth over the years can lead fibroids to become even more problematic during perimenopause and beyond, not diminish as expected.

"The message women get is if you can hang on until menopause, the fibroids will get better," says Dr. Elisa Jorgensen, a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital. "But many women can't wait that long, because symptoms become overwhelming. And some women get to menopause but still have the bulk of them."

Factors influencing growth

Also known as uterine leiomyomas, fibroids can be as small as the tip of a sewing needle or as large as a grapefruit. While their cause is unknown, the growths can run in families.

While conventional wisdom holds that fibroids are a younger woman's problem, recent research indicates it's possible for them to become newly apparent as menopause approaches. About one-third of newly diagnosed fibroids occur in women in their mid-to-late 40s, according to a February 2020 paper published in Menopause that cited a 2009 study involving nearly 1,800 women.

"A woman may have small fibroids earlier and not notice them, but with time — as she gets into her late 40s — the fibroids may be reaching the size where she does," Dr. Jorgensen says.

Another Menopause article, from November 2021, suggested small fibroids can keep growing after menopause is in the rearview mirror. The study tracked active fibroid growth in 102 postmenopausal women over five years using vaginal ultrasounds every six months. Researchers were surprised to observe that small fibroids grew more often than larger ones in these women. Additionally, fibroids grew faster and larger in participants who were overweight or obese.

Hormone considerations

Hormone therapy is another factor that increases the likelihood fibroids will develop or worsen with age, Dr. Jorgensen says. Because fibroids are sensitive to estrogen, women who take the hormone to allay menopausal symptoms may face this trade-off. On the other hand, doctors may prescribe combination estrogen-progestin birth control pills for pre- and peri-menopausal women with symptomatic fibroids. "They disrupt the body's natural hormone cycle, so they're not stoking the fire," she explains.

Treatment options after menopause

Treatments for other health conditions may also influence older women's fibroid symptoms. Abnormal bleeding, for example, usually eases as menopause arrives even if other symptoms linger. But it often won't for women who need to take an anti-clotting drug.

"Even if bleeding goes away," Dr. Jorgensen says, "fibroids may still be pressing into the bladder, so women will still experience symptoms like urinary frequency, incontinence, and back pain, among others. Fibroids can take up space that prevents the bladder from expanding, so you need to go to the bathroom more frequently and are more likely to leak urine."

Beyond the consequences of intense symptoms, fibroids that continue to grow noticeably after a woman reaches menopause raise the possibility of cancer, she notes. "For these expanding fibroids I would monitor their growth and may recommend surgically removing them," she says. "It's very uncommon for a fibroid to develop into cancer, but I'd want to make sure."

Surgical removal of fibroids, called myomectomy, joins hysterectomy as the two procedures doctors often advise for women seeking fibroid treatment after menopause, Dr. Jorgensen says. While an array of other techniques are available to treat fibroids, most don't work as well in women who have reached menopause because of the complex interplay between hormone levels and fibroid growth.

"If you're past menopause, you're generally not going to be able to take advantage of most other treatments that shrink fibroids," she says. That's because post-menopausal fibroids will presumably have done any possible shrinking once the body's estrogen production drops, so additional therapies aimed at blocking estrogen won't make a difference.

Image: © wildpixel/Getty Images

About the Author

Maureen Salamon, Executive Editor, Harvard Women's Health Watch

About the Reviewer

Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.