How the body’s internal clocks influence heart health

Strategies that sync with our innate circadian rhythms may improve the treatment of heart disease.

- Reviewed by Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

For most people, the word circadian — which comes from the Latin phrase circa diem, meaning “about a day” — refers to the 24-hour cycle that governs when we sleep and wake up. But circadian rhythms are hardwired into virtually every cell of the body, governed by a master clock in the brain that synchronizes clocks in tissues and organs, including the heart. While these clocks are tuned to daily light-dark cycles, they’re also influenced by behavior: sleep, eating, physical activity, and stress.

A state-of-the art review published July 15, 2025, in the European Heart Journal pulls together the latest science on how the body’s internal clocks regulate the heart and blood vessels, and how disruptions — whether from shift work, poor sleep, or unhealthy habits — can raise the risk of cardiovascular disease.

“When your sleep, eating, and exercise patterns are out of whack relative to your circadian rhythms, that can lead to an array of physiological changes that contribute to increased cardiovascular risk,” says Dr. Frank A.J.L. Scheer, who directs the Medical Chronobiology Program at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He and colleagues investigate the potential health consequences of circadian misalignment by studying volunteers in controlled environments. The researchers manipulate factors such as light, temperature, and when the volunteers eat, exercise, and sleep.

Monday morning heart attacks

As the review notes, heart attacks are about three times more likely to occur in the morning compared to the late evening. Dr. Scheer’s earlier research helped explain why: Among other factors, levels of a protein that makes blood clot more easily peaks around 6:30 a.m. and slowly drops over the next 12 hours — a fluctuation that’s driven by the circadian system. Studies also show that heart attacks occurring between midnight and 6 a.m. tend to cause more damage to the heart muscle and lead to worse long-term outcomes.

Heart attacks are more likely to occur on Mondays than any other day of the week. Why? On the weekends, people tend to stay up later than usual and then sleep in the next day, which experts refer to as “social jet lag.” On Monday morning, when they have to wake up early again for work, the resulting mismatch between their social and biological clock can cause subtle changes in blood pressure, hormone secretion, and metabolism that raise heart attack risk.

A similar phenomenon occurs every spring, when we set our clocks forward one hour for daylight savings time. Heart attacks are also more common during the first week of daylight savings time — especially on that first Monday after the switch.

Best times to eat and exercise?

Many studies show that people who work the night shift face higher rates of cardiovascular disease, likely in part because of circadian misalignment. But eating only during the daytime — right before and after their shift — may help shift workers avoid that risk, as Dr. Scheer’s team reported in the April 8, 2025, issue of Nature Communications. Their earlier research showed nighttime eating increases levels of hunger hormones versus satiety hormones and also slows metabolism, which may explain the increased risk of obesity among people who tend to eat more at night rather than during the day.

Popular advice cautions against exercising later in the day, especially at night, as the rise in heart rate and body temperature from a workout could make it harder to fall asleep. While that may be true for intense exercise within an hour of bedtime, afternoon and evening exercise seems to lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels more than morning exercise, according to some research.

“Most of the evidence supports the benefit of eating early in the day but exercising later in the day,” says Dr. Scheer.

Medication timing

The review also touches on the concept of chronotherapy — tailoring treatment to the body’s natural rhythms. Some medications are already prescribed with timing in mind. For example, short-acting statins such as simvastatin (Zocor) and pravastatin are typically taken at night to match the body’s peak cholesterol production. But for more potent statins such as rosuvastatin (Crestor), timing doesn’t matter. If your blood pressure tends to rise at night or in the early morning, taking blood pressure drugs at bedtime may help to blunt dangerous morning surges. But so far, there’s little or mixed evidence that any of these timing changes actually make a difference in terms of heart-related problems.

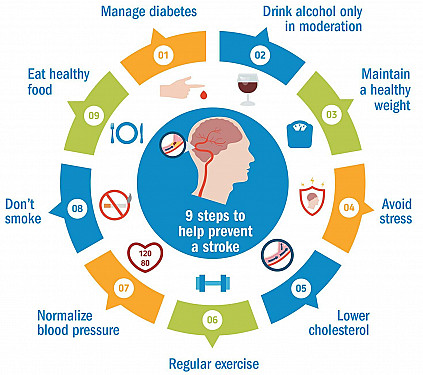

What you can doAs researchers continue to refine our understanding of circadian medicine, here are some steps you can take to stay in sync with your body’s internal clock. Front-load your calories in the first half of the day. Your metabolism is more efficient during the day versus the night. Exercise regularly, but time it right. An intense workout close to bedtime may disrupt sleep, but afternoon and evening exercise may be beneficial for your heart. Get morning sunlight. Exposure to bright light in the morning helps reinforce your circadian clock. Keep a consistent sleep schedule. Go to bed and wake up at roughly the same time each day, even on weekends. Limit evening screen time. Blue light from devices may interfere with your body’s preparation for sleep. Discuss medication timing with your doctor. Ask whether the timing of your medications might affect their effectiveness. |

Image: © Ridofranz/Getty Images

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.