Opioids for acute pain: How much is too much?

Two recent articles have again highlighted how often opioid pain relievers — medications like oxycodone and hydrocodone — are excessively prescribed in the US for acute pain, sometimes for vulnerable populations and sometimes for conditions for which they are probably not even indicated.

The first paper, by authors at Boston Children’s Hospital, evaluated visits to the emergency department by adolescents and young adults (ages 13 to 22) over an 11-year period from a nationwide sample. About 15% of patients — roughly one in six — were prescribed an opioid, with high rates seen for ankle sprains, hand fractures, collarbone fractures, and particularly dental issues, for which an incredibly high 60% of patients in this age group received an opioid.

Speaking of dental issues, the second paper compared opioid prescribing by dentists in the US and England. In this study, the researchers looked at opioid prescriptions in 2016, and the numbers are shocking. In the US, 22% of prescriptions written by dentists were for opioids, compared with just 0.6% for British dentists, and US dentists prescribed about 35 opioids per 1,000 population, compared to just 0.5 opioid prescriptions per 1,000 population in England. Additionally, the opioid prescribed in England was a relatively weak codeine-like drug, whereas in the US the majority of prescriptions were for hydrocodone, a stronger opioid with greater abuse potential.

When does an opioid prescription make sense?

It is simply impossible that pain experienced by people in the US is that staggeringly different than in the UK. So why the discrepancy? While it is possible that pain is being undertreated in the UK and more adequately treated in the US, I don’t believe that to be the case. The difference is that, in the US, prescribers were reassured for years that opioids were a safe and effective way to treat pain. And yes, they are effective, but as evidenced by the vast increase in opioid-related overdose deaths seen in the country over the past decade, they are not safe.

On the other hand, medications like acetaminophen and ibuprofen — those over-the-counter pain medicines that you can get at any supermarket — actually work amazingly well for acute pain. As an example, a large survey study of over 2,000 patients who underwent a range of dental procedures discovered that the vast majority experienced adequate pain relief with over-the-counter or non-opioid prescribed pain medications. And similar studies are abundant. Another study looked at patients treated for low back pain in the emergency department and found no difference in pain after five days, whether the patient was treated with an anti-inflammatory medicine (naproxen) or if an opioid was added. It just didn’t make a difference, so why take the risk?

Yet another study evaluated variation within the US for treatment of ankle sprains. Over 30,000 patients were studied. On average, about a quarter of patients received an opioid prescription, but the state-level differences were astounding, ranging from under 3% in North Dakota to 40% in Arkansas! All for a condition that, in general, should get better with ice, elevation, and a brace.

Of course, there are times when the over-the-counter medications are not going to be sufficient to treat acute pain. In those situations, the goal should be to take the non-prescription medications first, and then add an opioid only when the pain is unbearable. Typically, this period of severe pain is in the first three days after a surgery or trauma. For example, colleagues in my department evaluated opioid consumption in the days after suffering an acute fracture. Most patients needed only about six pills of oxycodone.

The same trend is seen after surgery. A large study of six other studies found that between two-thirds and 90% of post-operative patients reported unused opioids after their surgery, and as many as 71% of the tablets went unused. We therefore subscribe to the recommendations of the Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network (OPEN) program in Michigan, which recommends relatively small opioid prescriptions after surgery, such as 10 pills after having your appendix removed or hernia repaired, and just five for procedures like a breast biopsy. Patients do fine, even with these smaller numbers of pills, and are at less risk of developing long-term opioid use.

What to be aware of for teenagers and young adults who get an opioid prescription

My general recommendation for opioid-naïve patients, regardless of age, is the following: if you have a simple problem, like a sprain or a dental procedure, or even back pain, do whatever you can to avoid an opioid. Ask your doctor about which over-the-counter pain treatments you can safely take and maximize those. For more severe pain, such as from fractures or after surgery, use the minimum number of opioids needed to tolerate the pain, then back off once the pain is bearable and continue with the non-prescription treatments.

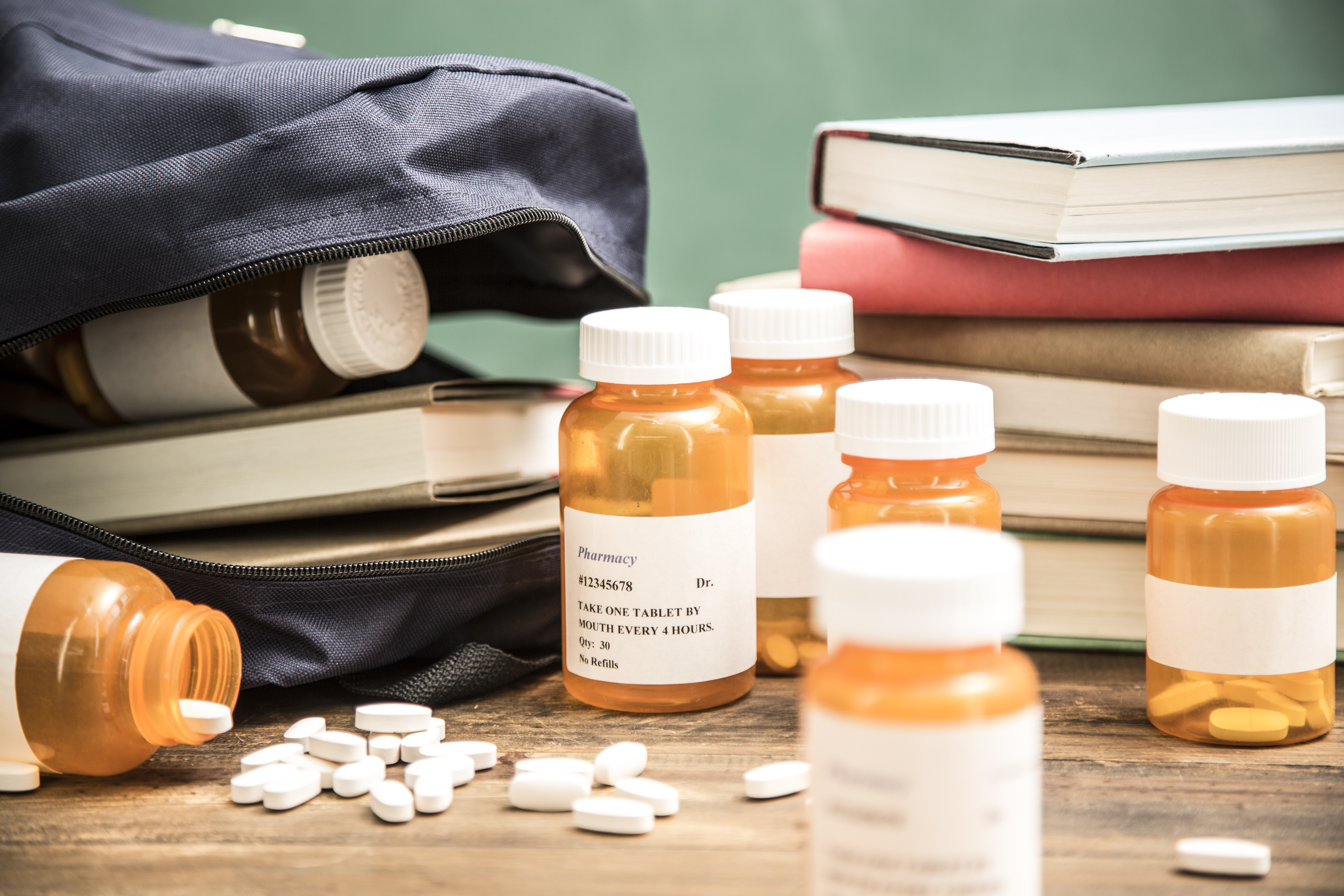

For adolescents and young adults, extra caution is needed. The adolescent brain is developmentally predisposed to developing addiction, and therefore at high risk. Although opioid misuse among teens is decreasing, it still is a major problem. Among high school seniors, past-year misuse of pain medication was 3.4% in 2018, and about a third of high school seniors thought that these drugs are easily accessible. It is therefore paramount to protect adolescents from these medications. If prescribed, they should ideally be stored securely and dispensed by a parent or guardian following the appropriately prescribed schedule. Education about the medicine, and the dangers of being dependent on the medication, is essential. This is also a great time for parents to talk to their children about drug use in general.

What to do with leftover pills

When the acute pain from those first few days is gone, if there are leftover opioid pills, discard them safely. I cannot reiterate this enough. About two-thirds of adolescents who misused opioids got them from friends or family for free. There are lots of places to safely discard pills. In fact, the Drug Enforcement Administration offers a website that lists the closest bin locations. If one of those is not accessible, mix the medication with coffee grounds or dirt, seal it in a plastic bag, and dispose of it in the trash. Just be sure not to flush it down the toilet, as opioids and other drugs can contaminate the water supply.

About the Author

Scott Weiner, MD, MPH, FACEP, FAAEM, Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.