Shunning osteoporosis treatment isn’t a wise decision for most women

Forgoing drugs that slow bone loss to avoid rare side effects can be the wrong decision for your hips and spine.

Image: wildpixel/Thinkstock

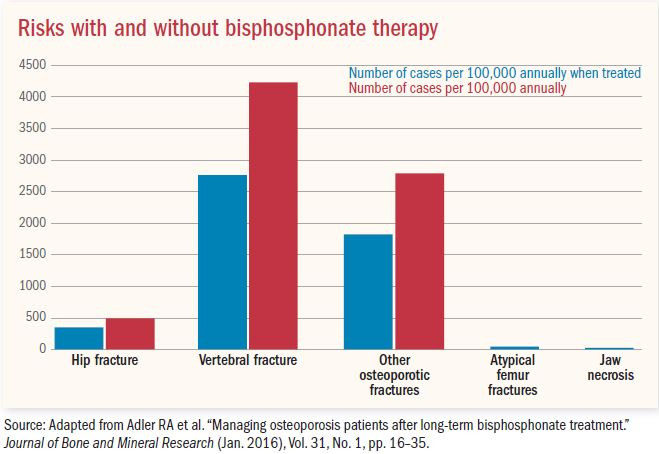

A front-page article in the June 1, 2016, edition of The New York Times carried this headline: "Fearing drugs' rare side effects, millions take their chances with osteoporosis." The article described a situation all too familiar to doctors. Women are declining prescriptions of bisphosphonates—drugs that slow the rate at which the body breaks down bone—or discontinuing the medications far earlier than recommended. In fact, according to a 2015 report in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, the rate of bisphosphonate use fell by half between 2008 and 2012. That article documented a wave of media coverage of scientific studies that reported two rare side effects—osteonecrosis (bone death) of the jaw and atypical fractures near the top of the femur (thigh-bone)—and suggested that the reports had kindled fears that had led women to abandon bisphosphonates.

"The perception of risk is so much greater than the actual risk," says Dr. Meryl LeBoff, director of the skeletal health and osteoporosis center at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women's Hospital. Compared with many other common diseases, we are fortunate that we have good therapies to reduce the risk of osteoporotic fractures by 70% at the spine and 40 to 50% at the hip. She points to statistics referenced in the New York Times article: for every 100,000 women taking a bisphosphonate, fewer than three will have osteonecrosis of the jaw and one will have an atypical femur fracture, but 2,000 will have avoided an osteoporotic fracture.

Learn your personal risk of fractures

While statistics like the above are good for making public health assessments, they provide only a rough idea of your personal risk. If you have osteoporosis, taking stock of your individual risk factors—for hip and spine fracture as well as for jaw necrosis—can help you make a more informed decision.

The most direct way to determine your risk of fracture is by having your bone density measured at the hip and spine with dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). A DEXA scan is recommended for women ages 65 or older and for women ages 50 or older who have broken a bone recently. (At least 50% of women who have a hip fracture have already broken another bone.) Your doctor may also recommend a DEXA scan if you smoke, consume an average of three or more alcoholic drinks a day, have a low body mass index (BMI), or take a corticosteroid medication—all of which may contribute to bone loss. The result, expressed as a number called a T-score, compares your bone density with that of a healthy younger woman. A T-score of –2.5 or lower—the definition of osteoporosis—is an indication you may need a prescription for a medication to slow or arrest bone loss.

If your DEXA scan indicates you have osteopenia—a T-score between -1.0 and -2.5—your clinician may use the FRAX calculator. The FRAX score incorporates information about your hip bone density and other risk factors to estimate your 10-year fracture risk. In general, if your 10-year fracture risk is at least 3% for hip fractures or at least 20% for other major osteoporotic fractures, you should consider taking medication to prevent bone loss or increase bone density to avert future fractures.

What's your risk of complications?

In response to concern about jaw necrosis, 14 professional organizations of dentists, physicians, and bone scientists formed the International Task Force on Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. The task force reviewed all the research on that condition published from 2003 to 2014. They determined that each year, .001% to .01% of people taking oral bisphosphonates like alendronate (Fosamax), ibandronate (Boniva), or risedronate (Actonel) develop jaw necrosis—a number only slightly higher than among people not taking those medications.

The risk was much higher—15%—for cancer patients whose treatment included intravenous infusions of zoledronate (Zometa), a bisphosphonate, or injections of denosumab (Prolia), a monoclonal antibody that also inhibits bone resorption. The task force also identified other risk factors for jaw necrosis, including poor dental hygiene, wearing ill-fitting dentures, and undergoing oral surgery. Certain conditions, including diabetes and inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, and some medications, particularly corticosteroids and drugs that inhibit blood vessel growth, also increase the risk.

Atypical femoral fractures are rare—about three to 50 in 100,000 people taking bisphosphonates annually. Researchers are searching for factors that place some women at increased risk. In a review of the studies through 2014, the International Task Force on Atypical Femoral Fractures determined that people who had such fractures had taken bisphosphonates an average of seven years. Being of Asian descent and taking corticosteroids were also linked to a higher risk in some studies.

Points to ponder

If you have low bone density and are debating whether to take a bisphosphonate, you may consider the following:

Osteoporotic fractures can be debilitating. If you accumulate several vertebral fractures, you may lose height, develop a hump, and have less room for your abdominal organs. It will become more difficult to breathe, and you may develop digestive problems and incontinence. A hip fracture can necessitate months of rehabilitation therapy and can render you unable to walk unassisted, even after the bone has mended. Hip fracture is also linked with an increased likelihood of being admitted to a nursing home and an elevated risk of premature death.

Medications can markedly reduce fracture risk. For example, taking zoledronate or denosumab can decrease the risk of hip fractures by 40% and spine fractures by about 70%. For women with low bone density, alendronate is associated with a reduction of about 50% for hip and spine fractures and 23% for wrist, ankle, and other bone fractures. (See "Effectiveness of common osteoporosis medications.")

Effectiveness of common osteoporosis medications |

|||||

|

Osteoporosis medication |

Reduced risk of fractures? |

||||

|

Generic name |

Brand name(s) |

Form |

Hip |

Vertebral |

Other bones |

|

alendronate |

Fosamax |

Oral |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

ibandronate |

Boniva |

Oral |

Unproven |

Yes |

Yes |

|

risendronate |

Actonel, Atelvia |

Oral |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

denosumab |

Prolia |

Semiannual injection |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

teriparatide |

Forteo |

Daily injection |

Unproven |

Yes |

Yes |

|

zolendronate |

Reclast |

Annual intravenous infusion |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Source: Adapted from Adler RA et al. "Managing osteoporosis patients after long-term bisphosphonate treatment." Journal of Bone and Mineral Research (Jan. 2016), Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 16–35. |

|||||

Risk of jaw necrosis and atypical thigh fracture is lower when use of bisphosphonates is limited. For most women, bisphosphonate treatment ends after five years of oral therapy or after three annual intra-venous infusions of zolendronate. However, the drugs' effects remain for several years after therapy is discontinued.

Your risk of developing jaw necrosis is negligible if you are healthy. The American Dental Association has decided against recommending that dental patients discontinue bisphosphonate therapy before having an extraction or dental implant.

You can further reduce your risk through vigilant dental care. Brush twice a day, floss daily, and have regular dental cleanings. To further minimize risk, choose the least invasive dental procedures possible—a root canal instead of an extraction, or a bridge instead of an implant.

The optimal duration of treatment varies among individuals. Talk to your doctor about how long your osteoporosis therapy should be continued.

The take-away message

Osteoporosis is a common disease and fragility fractures increase dramatically with age. "The occurrence of a fracture can be devastating, and women can benefit from the effective therapies that markedly reduce their risk of osteoporotic fractures. The current situation— in which women who have had fragility fractures or are at high risk of fractures are discontinuing therapy or are not even being treated—is considered a crisis," Dr. LeBoff says.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.