When do you really need an angioplasty and stenting?

These standard treatments for most heart attacks may not be necessary in other situations involving chest discomfort.

- Reviewed by Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

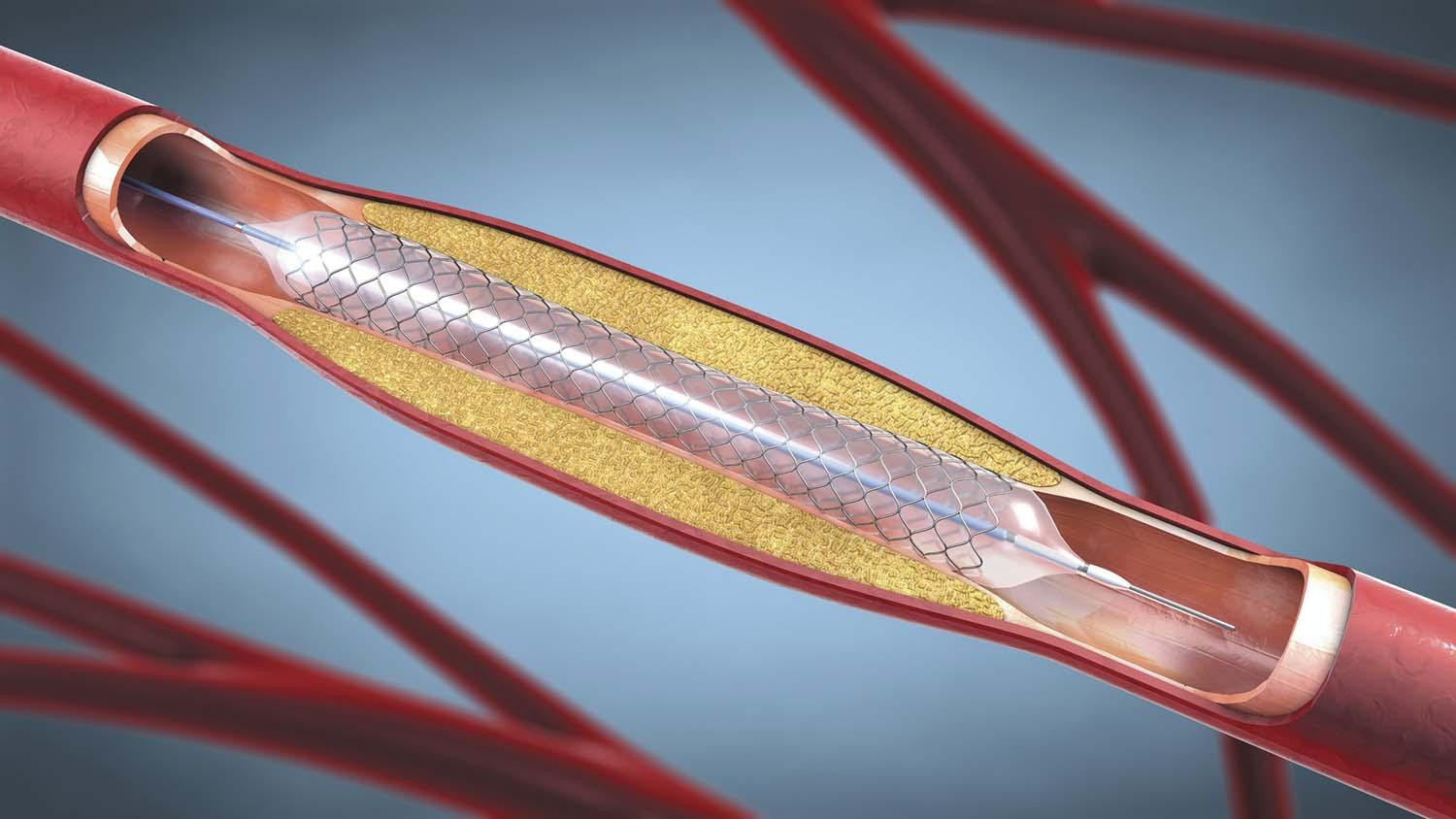

Coronary artery disease occurs when cholesterol-laden debris narrows the arteries that supply blood to the heart. The most common form of heart disease, it is treated with lifestyle changes and medications. However, sometimes people also need a procedure called angioplasty to open a blocked or narrowed artery and improve blood flow to the heart, along with placement of a stent to hold the artery open.

To perform an angioplasty, a specially trained heart doctor inserts a thin flexible plastic tube (catheter) with a tiny balloon on its tip into a blood vessel in the patient’s wrist or arm.

The doctor inflates the balloon to widen the clogged artery. The doctor then puts in place a small wire mesh tube called a stent. The stent provides scaffolding to help prevent the artery from narrowing again. Some stents also release a medication into the artery to help keep it open.

When do you need an angioplasty and stent procedure, and when might it not be the best treatment option? Here’s a look at the different clinical scenarios.

Stable angina

Angina (chest pain) is a common symptom of coronary artery disease. It occurs when fatty plaque (atherosclerosis, sometimes called “hardening of the arteries”) narrows the coronary arteries, slowing blood flow to the heart.

During exercise or periods of emotional stress (when blood pressure and heart rate both go up), the body’s increased demand for blood may outpace the heart’s supply.

The resulting drop in blood flow to the heart muscle triggers discomfort. The feeling might initially occur only with significant exertion and later become more frequent with even less physical effort.

Doctors divide angina into two types: stable and unstable. Stable angina is more predictable. You usually experience it when performing a specific exercise (for instance, walking uphill) or when experiencing emotional stress (such as arguing with someone). The pain usually lasts five minutes or less and subsides with rest.

“Stable angina doesn’t feel surprising when it occurs, and the bouts of discomfort tend to be alike and generally predictable,” says cardiologist Dr. William Boden, scientific director of the Clinical Trials Network of the VA New England Healthcare System and senior lecturer in medicine at Harvard Medical School.

If the chest discomfort with exertion or stress is infrequent, doctors often attempt to alleviate such symptoms and minimize episodes through lifestyle modifications and medications. Lifestyle changes can include weight loss, adopting a heart-healthy diet, managing stress, and adjusting your regular exercise routine. These help modify the main risk factors that contribute to angina: weight gain, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure.

“If the chest discomfort increases in frequency or severity, it may be a warning of something more serious, such as unstable angina or possibly a heart attack,” says Dr. Boden. “In such cases, you need to immediately contact your doctor or seek emergency care.”

Almost everyone with coronary artery disease needs medication to lower LDL (bad) cholesterol, most often starting with a statin. Other drugs may include nitrates (such as nitroglycerin to relieve or prevent chest pain), a calcium-channel blocker (which relaxes and widens blood vessels), a beta blocker (which slows the heart rate), and an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin-receptor blocker to maintain normal blood pressure.

In most cases of stable angina, angioplasty and stenting are not necessary. “For most people, lifestyle changes and medication control angina symptoms just as effectively as angioplasty,” says Dr. Boden. A study scheduled to be published this year in the European Heart Journal also found that using medication to treat stable angina as initial therapy did not increase the risk for heart attack compared with going straight for an angioplasty and stent.

“If medication doesn’t relieve symptoms, then you can discuss with your doctor getting a stent procedure for symptom relief,” says Dr. Boden.

Unstable angina

In comparison to stable angina, unstable angina is a serious condition that requires immediate attention, as it’s often a warning sign of a potential heart attack. With unstable angina, chest pain occurs repeatedly and unexpectedly, often at rest and sometimes even during sleep. The pain is usually severe, lasting longer than 15 to 20 minutes, and usually doesn’t go away with rest.

“You need to seek immediate care if you have any symptoms of unstable angina, as it signals blockage or a severe narrowing of a coronary artery,” says Dr. Boden. “Most often, a fatty plaque has ruptured, prompting the formation of a blood clot in the artery, which significantly restricts blood flow to the heart.”

Treatment depends on the person’s diagnosis. Patients are typically given medications like blood thinners and antiplatelet drugs to prevent a blood clot from forming in a coronary artery, and other drugs to manage the pain. “If the person’s condition stabilizes, then the doctor may move forward with conservative treatments of medications and lifestyle changes, like with stable angina,” says Dr. Boden.

However, if a significant blockage is suspected, a cardiac catheterization is done to determine the extent of the artery blockage. This involves inserting a catheter and guiding it to the heart, as described earlier. The doctor can then identify coronary artery blockages and assess blood flow.

“If there is 70% or higher blockage, you likely will receive an angioplasty and stent,” says Dr. Boden. “If not, your doctor will likely proceed with the lifestyle and medication route and monitor your condition.”

Do too many people have unnecessary angioplasty and stents?A 2023 report from the Lown Institute, an independent health care think tank, found that more than 229,000 unnecessary stents were placed in Medicare patients from 2019 to 2021, accounting for more than one in five stent procedures performed during that period. Why do some people undergo unnecessary angioplasty and stent procedures? The reason may be twofold, according to Dr. William Boden, lecturer in medicine at Harvard Medical School. “Doctors may err on the side of caution and recommend them if there is concern about any amount of blockage,” he says. “A doctor might see less than 70% blockage—when many people don’t even experience symptoms of angina—and say they can fix that with an angioplasty and stent, whereas the patient often hears they can be cured,” says Dr. Boden. “But in these cases, the procedures are a Band-Aid fix and don’t address what caused the initial problem of blocked coronary blood flow.” Unnecessary angioplasty and stents also raise the risk of possible side effects like bleeding at the insertion site. There is also about a 1% risk of having a heart attack or stroke during or soon after the procedure. People must also take two antiplatelet drugs for at least six months to prevent clots from forming inside the stented artery, and those drugs also carry a potential risk of bleeding. |

Heart attacks

An angioplasty with stent placement is often the first-line treatment for a heart attack. When you experience symptoms of a heart attack — such as severe chest pain; shortness of breath; pain radiating to the jaw, neck, shoulder, or arm — you should go to the emergency room.

“Your care team will quickly determine if you need an urgent cardiac catheterization, during which you will usually get an angioplasty and stent if there is a blockage of 70% or more,” says Dr. Boden. “Ideally, the procedure should be done within 90 minutes to minimize heart muscle damage.”

This article is brought to you by HarvardHealthOnline+, the trusted subscription service from Harvard Medical School. Subscribers enjoy unlimited access to our entire website, including exclusive content, tools, and features available only to members. If you're already a subscriber, you can access your library here.

Image: © Christoph Burgstedt/Science Photo LibraryGetty Images

About the Author

Matthew Solan, Former Executive Editor, Harvard Men's Health Watch

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.