Choosing heart-healthy oils for home cooking

Canola and other seed oils are good choices, despite what some social media posts say.

- Reviewed by Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

Including more plant-based foods in your diet makes sense for a lot of reasons, including the fact that the fats found in plants (such as nuts, seeds, and olives) are mostly unsaturated. Decades of research demonstrates that consuming unsaturated fat in place of saturated fat (found mainly in animal-based foods such as butter, cheese, and meat) is linked to a lower risk of heart attack and death from heart disease.

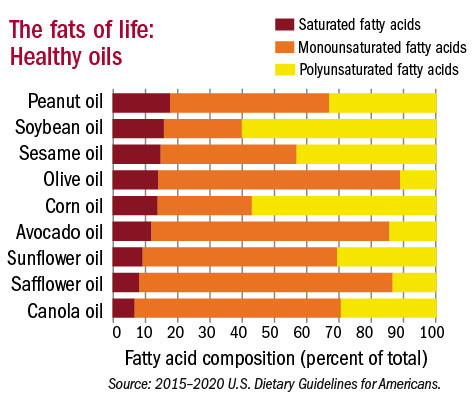

Olive oil, a key component of the heart-friendly Mediterranean diet, has long been touted as one of the healthiest fats to use for cooking. But it's just one of many plant-based oils that are rich in unsaturated fatty acids, which are liquid at room temperature (see "The fats of life: Healthy oils").

If you read social media, you may have run across posts and memes claiming that seed oils (such as canola, safflower, and sunflower oils) are responsible for a host of health problems, including obesity, diabetes, and even heart disease. But there's scant scientific evidence to support these claims, says Dr. Guy Crosby, an adjunct associate professor of nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Back in 2015, he wrote an article for Harvard's Nutrition Source addressing the misconceptions about the safety of canola oil, the second most commonly consumed oil in the United States after soybean oil. "Even to this day, I get scathing emails from random people telling me how terrible canola oil is," he says.

Canola oil concerns?

It's true that seed oils count as processed foods, since manufacturing them involves crushing the seeds and then extracting the oil with hexane, a solvent. But for the average person, any residual traces of this chemical in oils and other foods are dwarfed by exposures from other sources, such as gasoline fumes.

Another concern involves trans fatty acids, which are linked to a heightened risk of heart disease. Canola oil — along with all other liquid oils sold in supermarkets — does contain small amounts of trans fat. These form during the deodorizing process that gives oils a bland, neutral flavor. However, the amount of trans fats per one-tablespoon serving is so low, the FDA allows these oils to include a "contains zero trans fats" claim on their labels.

In terms of heart health, canola oil has several favorable attributes, says Dr. Crosby. It's a decent source of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), the main vegetarian source of essential omega-3 fatty acids. Like EPA and DHA (the omega-3 fats found in fatty fish), ALA has anti-inflammatory and other effects thought to benefit cardiovascular health. Canola oil also contains phytosterols, which are compounds that occur naturally in plants that may help lower cholesterol.

For these reasons, people should consider canola oil a safe and healthy option for saut'ing, stir-frying, roasting, and baking. It's also less expensive than olive oil, although cost isn't the only consideration. Some people avoid olive oil because of its reputation for having a grassy, fruity, or peppery flavor that they don't necessarily want in certain dishes, says Dr. Crosby. However, most supermarket olive oil has a fairly mild flavor, and once you heat it up, all the volatile flavor compounds disappear in about 10 minutes, he adds.

Home cooking vs. processed food

Dr. Crosby suggests keeping several different oils in your cupboard for varied uses. For instance, you might want extra-virgin olive oil to use in salad dressings and for dipping bread, and toasted seed or nut oils (such as sesame or walnut) for drizzling on vegetables or other dishes. For cooking, soybean is a fine alternative to canola oil, as is what's labeled as "vegetable oil," which typically contains soybean oil but may contain a blend of different oils.

Of course, some people get a lot of their calories from processed or restaurant-prepared foods, including deep-fried foods — and that's where the real risk lies. Repeatedly heating unsaturated oils up to high temperatures creates trans fats and other harmful substances, Dr. Crosby explains. Factories and restaurants don't change their oil often enough to get rid of those compounds, which likely contributes to the strong link between frequent fried food consumption and heart disease.

Image: © Noel Hendrickson/Getty Images

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.