Advice about daily aspirin

Should you take this anti-clotting drug to prevent a heart attack or stroke?

In the late 1980s, many middle-aged adults began taking aspirin on a regular basis, following findings from a famous Harvard study (see "The ascent of aspirin"). Aspirin helps prevent blood clots that can restrict blood flow and trigger a heart attack or stroke. But there’s a price to pay for that cardiovascular protection — a heightened risk of bleeding.

In the late 1980s, many middle-aged adults began taking aspirin on a regular basis, following findings from a famous Harvard study (see "The ascent of aspirin"). Aspirin helps prevent blood clots that can restrict blood flow and trigger a heart attack or stroke. But there’s a price to pay for that cardiovascular protection — a heightened risk of bleeding.

"The benefit of a taking a daily low-dose aspirin always has to be counterbalanced with the risk of bleeding, which is usually minor but sometimes serious," says Dr. Christopher Cannon, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. Over the past three decades, we’ve learned a lot more about aspirin’s benefits and risks in a broad range of people, including those with certain health conditions and older adults.

The ascent of aspirinIn the early 1980s, more than 22,000 male physicians without heart disease or a history of stroke volunteered for what became a landmark trial, the Physicians’ Health Study. For five years, they took 325 milligrams (mg) of aspirin or a placebo every other day. During the five years, those taking aspirin had 44% fewer heart attacks than those taking a placebo. But there were some downsides, including more bleeding ulcers and a slightly increased risk of bleeding in the brain among the aspirin users. Subsequent studies showed that even low-dose aspirin (81 mg) can cause bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract, especially in people who are 65 and older. Compared with ischemic strokes (caused by clots), hemorrhagic strokes (caused by bleeding) are far less common, accounting for just 13% of all strokes. But aspirin use raises the risk of hemorrhagic strokes, especially in people with high blood pressure. |

Today, around half of Americans ages 45 and older take a daily low-dose aspirin. For some of these people, it’s a good idea. Others should consider stopping, as the risks likely outweigh the benefits. But many people fall somewhere in the middle. Here’s the latest about who should consider aspirin to prevent heart attacks and strokes — and who should avoid it (see "An aspirin algorithm" for a summary).

Remember: even if you’re in the "yes" category — and especially if you fall under the "maybe" classification — never take (or stop taking) daily aspirin without first discussing it with your doctor.

An aspirin algorithmThis table provides a quick summary of the current advice about aspirin; see the main story for more details. |

|||

|

Prevention |

Condition |

Ischemic risk |

Start low-dose aspirin? |

|

Secondary |

ASCVD |

High |

YES |

|

Primary (preventing a first heart attack or stroke) |

Imaged vascular disease |

High |

MAYBE |

|

Diabetes |

High |

MAYBE |

|

|

Low |

NO |

||

|

High bleeding risk |

High |

MAYBE |

|

|

Above age 70 |

Low or high |

PROBABLY NOT |

|

YES: People who’ve already had a heart attack or stroke caused by a blood clot (ischemic stroke). For these people, a daily aspirin often makes sense. This practice, known as secondary prevention, applies to anyone with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). That includes all conditions caused by plaque buildup (atherosclerosis) anywhere in the body — not just heart attacks and ischemic strokes, but also transient ischemic attacks (TIAs, or ministrokes), angina (chest pain from narrowed heart arteries), and peripheral artery disease (plaque in leg arteries). Anyone who’s had coronary bypass surgery or a stent implanted to restore blood flow to the heart also is considered to have ASCVD.

MAYBE: People with evidence of ASCVD on an imaging test. This group of people includes those who are at high risk of a heart-related problem based on visual evidence of plaque in their arteries. The tests include a coronary artery calcium scan, a CT scan done for another reason (such as screening for lung cancer or a pulmonary embolism), or an ultrasound of the neck arteries (carotid ultrasound). There aren’t any large studies showing that aspirin helps these people, Dr. Cannon cautions. The benefit probably outweighs the risk, but the calculation will depend on your individual situation, he adds.

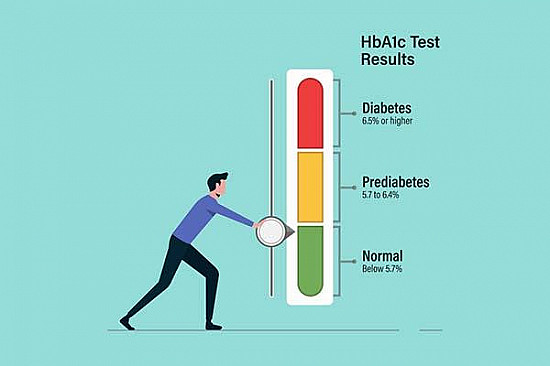

MAYBE: People with diabetes. In general, people ages 40 to 70 with diabetes who face a high risk of heart disease should consider low-dose aspirin. You can estimate your 10-year risk of ASCVD with this calculator created by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology (find it at /heartrisk). High risk is defined as a 10-year risk of 20% or higher.

MAYBE: People at risk of both clotting and bleeding. For the most part, people without ASCVD at risk of bleeding should not take daily aspirin. That includes anyone with a history of bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract or elsewhere in the body (for example, serious nosebleeds or blood in the urine); a stomach ulcer (peptic ulcer disease); low blood platelets (thrombocytopenia); blood clotting disorders (coagulopathy); and people who take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) routinely, such as people with arthritis or other painful inflammatory conditions. The one exception is people with a 10-year ASCVD risk score of 20% or higher, in which the cardiovascular risk may outweigh the bleeding risk. Taking a proton-pump inhibitor such as omeprazole (Prilosec) along with aspirin can help diminish the chance of gastrointestinal bleeding, says Dr. Cannon.

PROBABLY NOT: Anyone over 70 without ASCVD. Because bleeding risk rises with age, most people without ASCVD (see the first category above) over 70 shouldn’t take a daily aspirin. The most recent study in people older than 70 found no significant benefit but an increased risk of bleeding. If you started taking aspirin in middle age, that may have been a good idea at the time. But once you reach 70, the bleeding risk of daily aspirin may outweigh any protection against heart attack or stroke, so you should check with your doctor about whether you should continue.

Image: © Creatas/Getty ImagesAbout the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.