Chronic otitis media, cholesteatoma, and mastoiditis

- Reviewed by Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

What is chronic otitis media?

Chronic otitis media describes some long-term problems with the middle ear, such as a hole (perforation) in the eardrum that does not heal, or a middle-ear infection (otitis media) that doesn't improve or keeps returning.

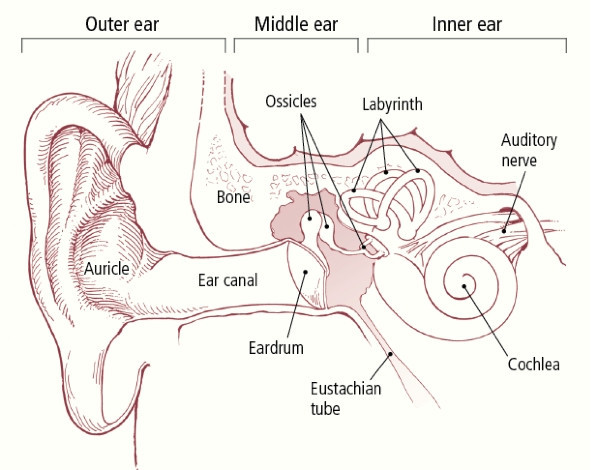

The middle ear is a small bony chamber with three tiny bones - the malleus, incus, and stapes - covered by the eardrum (tympanic membrane). Sound is passed from the eardrum through the middle-ear bones to the inner ear, where the nerve impulses for hearing are created. The middle ear is connected to the back of the nose and throat by the eustachian tube, a narrow passage that helps to control the air flow and pressure inside the middle ear. The middle ear can become inflamed or infected when the eustachian tube becomes blocked, for example, when someone has a cold or allergies. When fluid remains in the middle ear, the condition is called chronic serous otitis media.

Sometimes a middle-ear infection causes a hole (perforation) in the eardrum. A hole that does not heal within six weeks is called chronic otitis media. This problem can take one of three forms:

- Non-infected chronic otitis media – There is a hole in the eardrum but no infection or fluid in the middle ear. This condition can exist indefinitely. As long as the ear remains dry, nothing necessarily needs to be done for this condition. Repairing the hole is only necessary to improve hearing or to prevent infection.

|

|

- Suppurative (filled with pus) chronic otitis media – This happens when there is a hole in the eardrum and an infection in the middle ear. Cloudy and sometimes foul-smelling fluid drains out through the opening. Treatment with antibiotics (by mouth or with ear drops) usually helps to clear the active infection.

- Chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma – A persistent hole in the eardrum sometimes can lead to a cholesteatoma, a growth (tumor) in the middle ear made of skin cells and debris. A cholesteatoma also can form when there is no hole, such as when the eustachian tube is blocked. Cholesteatomas can cause hearing loss and are prone to get infected, which can cause ear drainage. Cholesteatomas can grow large enough to erode the middle ear structures and the mastoid bone behind the middle ear.

Children are more likely to get middle-ear infections. Because of this, they also are more likely to develop chronic otitis media. Doctors believe that children have an especially high risk of all types of ear infections because of several factors, including:

- immature immune (infection-fighting) system

- undiagnosed allergies

- eustachian tubes that are smaller and less angled compared to those of adults

- unusually large or infected adenoids (masses of infection-fighting tissue in the back of the nose, near the opening of the eustachian tubes)

- exposure to cigarette smoke

- attendance at day care.

Problems with the middle ear, such as fluid in the middle ear, a hole in the eardrum, or injury to the small middle-ear bones, can cause hearing loss. In rare situations, infections in the middle ear can spread deeper inside the inner ear, causing a sensorineural hearing loss and dizziness. Rare, but serious, complications include brain infections, such as an abscess or meningitis. A chronic infection and a cholesteatoma also can cause injury to the facial nerves and facial paralysis.

Symptoms of chronic otitis media

A person can have chronic otitis media caused by a persistent hole in the eardrum for years with no symptoms or only mild hearing loss. There may be mild ear pain or discomfort. When the middle ear is infected, fluid will drain from the ear and hearing loss can worsen.

Symptoms that can be a sign of a more serious condition, and that require immediate attention, include

- severe pain, dizziness, and facial nerve injury (facial weakness)

- swelling, tenderness, and redness behind the ear, which may indicate spread of infection to the mastoid bone (mastoiditis)

- fever, headache, and confusion.

Diagnosing chronic otitis media

The doctor will ask about a history of ear infections, treatments used, and any previous ear surgery. The doctor also will want to know about any medications being taken to treat an ear problem, including the type, dose, and length of treatment.

The doctor may suspect chronic otitis media based on a history of prior ear infections, persistent ear drainage, or both. To confirm the diagnosis, he or she will look inside the ear with a special light called an otoscope and may take a sample of drainage fluid to be examined in a laboratory.

In some cases, the primary care doctor may refer you or your child to an otolaryngologist, a doctor who specializes in treating disorders of the ears, nose, and throat. If the otolaryngologist suspects mastoiditis or a cholesteatoma, additional tests may be needed. These could include x-rays, a computed tomography (CT) scan, or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. If there is any concern that hearing may have been affected, it can be evaluated by a test called an audiogram.

Expected duration of chronic otitis media

How long symptoms last varies. Antibiotic treatment of the infection causing the chronic otitis media may be enough to stop the ear from draining. Sometimes, despite appropriate antibiotics, the infection continues, and surgery may be needed to remove the infected tissue and repair the eardrum perforation and any injury to the tiny bones in the ear.

Preventing chronic otitis media

One of the best ways to prevent chronic otitis media is to have any ear infection treated promptly. A child with chronic eustachian tube problems may need special tubes (tympanostomy tubes) inserted into his or her eardrums to prevent repeated ear infections by allowing air to flow normally in the middle ear.

After an infection clears up, a perforated eardrum may need to be repaired to prevent another infection.

Treating chronic otitis media

The goals of chronic otitis media treatment include

- resolving ongoing infection

- limiting drainage from the ear

- healing the eardrum (tympanic membrane)

- preventing recurrent infection to help avoid complications.

In many case, topical antibiotics are tried first. Most often, doctors choose a fluoroquinolone antibiotic solution, such as ciprofloxacin. For more severe infections, an oral antibiotic will be needed.

Also, the doctor will suction out the middle-ear fluid that is draining. Most infections will clear up with this treatment unless a cholesteatoma is present. A cholesteatoma can cause repeated infections and often must be removed with surgery.

A doctor may recommend surgery to repair a persistent hole in the eardrum. However, in some cases, the hole is left open because it can act like a tympanostomy tube to allow air to flow through the middle ear and possibly prevent more infections.

When a chronic ear infection spreads beyond the middle ear to the mastoid bone (the portion of bone behind the middle ear), a serious infection called mastoiditis can occur. Antibiotics given intravenously (into a vein) often can clear up this infection, but surgery may be necessary.

When to call a professional

Call your doctor immediately if you or your child develops a cloudy or foul-smelling discharge from one or both ears or has difficulty hearing. Also, seek emergency care for fever, swelling, tenderness, or redness behind the ear, persistent or severe ear pain, dizziness, headache, confusion, or facial weakness.

Prognosis

With prompt antibiotic treatment and ear aspiration, the outlook is excellent. About nine out of 10 patients are free of infection after this therapy. Surgery is not required in most cases, but may be necessary to correct a persistent eardrum perforation or to remove a cholesteatoma. After this surgery, the infection almost always goes away. Whether full hearing returns depends on the extent of damage and how well the ear heals after surgery.

Additional info

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/

American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery

https://www.entnet.org/

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

https://www.aap.org/

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.