Added sweeteners

Are high-fructose corn syrup and other sweeteners fueling the American obesity epidemic?

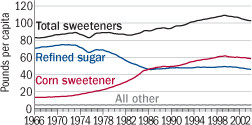

Americans have quite the sweet tooth. Our annual consumption of sweeteners has climbed sharply since 1980, peaking in the late 1990s. Sweetener intake has dropped a little since then, but it's still high — about 100 pounds annually per person.

During these same years, many more Americans — particularly children — have become overweight and obese. Added sweeteners may be one of the major reasons.

So what's the best approach? Avoid sugar? Avoid added sweeteners altogether? Stick to artificial ones that don't have calories? At this point, there are no clear answers. The best may be to follow that tired-but-true health-advice cliché: Everything in moderation.

Sucrose and fructose

The sugars — including honey, maple syrup, and corn syrup, as well as table sugar — are carbohydrates, that big, energy-packed group that also includes starches and cellulose. In the world of added sweeteners, they are sometimes referred to as the caloric, or nutritive, sweeteners. Structurally, they can be one of two types:

-

monosaccharides (simple sugars) — like fructose or glucose, which is what human beings and most other living things metabolize (burn for energy).

-

disaccharides — two monosaccharides put together; examples include maltose (two glucose molecules), lactose (galactose and glucose), and sucrose (glucose and fructose).

When you digest sucrose — whether it's from sugar cane or sugar beets (or, for that matter, maple sap) — it breaks down into 50% glucose and 50% fructose. High-fructose corn syrup is also made of glucose and fructose, but the two monosaccharides are simply mixed together, not bonded as a disaccharide. High-fructose corn syrup was first produced in the late 1960s, with the introduction of a new method (enzyme-catalyzed isomerization) that changes some of the glucose in corn syrup into fructose. It's available in three grades — HFCS-42, HFCS-55, and HFCS-90; the numbers indicate the percentage of fructose content.

High-fructose corn syrup is as sweet as sucrose, but less expensive, so soft-drink manufacturers switched over to using it in the mid-1980s. Now it has surpassed sucrose as the main added sweetener in the American diet.

|

Estimated per capita sweetener consumption

Source: USDA Economic Research Service Outlook Report No. SSS243-01 (August 2005) |

Is fructose to blame?

Fructose once seemed like one of nutrition's good guys. Despite being among the simplest of simple carbohydrates, it has a very low glycemic index. The glycemic index is a way of measuring how much of an effect a food or drink has on blood sugar levels; low glycemic index foods are generally better for you.

But fructose, at least in large quantities, may have some serious drawbacks. It has a low glycemic index because our metabolisms aren't designed to handle a lot of it at one time. In an article published in 2005 in Nutrition and Metabolism, University of Toronto researchers noted that for thousands of years, human fructose consumption was limited to fresh fruits in season. In the past 100 years or so, there's been a massive increase in our fructose intake, but we haven't gotten any better at metabolizing it.

Glucose, not fructose, is the mainstay of our energy production. Glucose metabolism occurs in cells throughout the body by the complex process of glycolysis and the Krebs cycle (the bane of every organic chemistry student's existence), ultimately yielding carbon dioxide and water. By contrast, fructose is metabolized almost exclusively in the liver. It's more likely to result in the creation of fats (lipogenesis): in particular, very low-density lipoproteins and triglycerides, both of which increase the risk for heart disease. Moreover, recent work has shown that fructose may have an influence on the "appetite hormones," leptin and ghrelin, that doesn't bode well for our waistlines. High levels of fructose may lower leptin and fail to depress ghrelin. Those changes would blunt sensations of fullness (satiety) and could lead to overeating.

Fruit-juice concentrates: Just empty calories

Fruit juices such as apple or white grape juice in concentrated form are widely used sweeteners. They're "fat mimetics" used to replace fats in low-fat products because they retain water and provide bulk, which improve the appearance and "mouth feel" of the food.

Although they may seem healthier and more natural than high-fructose corn syrup, fruit-juice concentrates also have high levels of fructose. Concentrated apple juice, for example, is 65% fructose, higher than the 55% fructose content of HFCS-55 that is used in soft drinks. And fruit-juice–concentrate sweeteners don't have the vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, and fiber of whole fruit. No less than sucrose or high-fructose corn syrup, fruit-juice concentrates are another way that empty calories get into our diets.

Artificial sweeteners

Artificial sweeteners sing a siren song of calorie-free and, therefore, guilt-free sweetness. The FDA-approved ones include acesulfame K (Sunett), aspartame (NutraSweet, Equal), neotame, saccharin (Sweet 'N Low, others), and sucralose (Splenda). All are intensely sweet. Some, like aspartame, are not completely calorie-free. Each gram has a few of them. But because it's so sweet (160–220 times sweeter than sucrose), you need very little, so the calorie count is negligible.

Saccharin goes way back. It was discovered in 1879 through work with coal tar derivatives and was originally derived from toluene, or methyl-benzene. It first became popular during the sugar shortages of World War I. Aspartame, discovered in 1965, is synthesized from the two amino acids, aspartic acid and phenylalanine. Sucralose, approved by the FDA in 1998, is a re-engineered sucrose molecule in which three chlorine atoms replace oxygen-hydrogen units.

There's a cyberspace cottage industry dedicated to condemning the artificial sweeteners, especially aspartame. Some fears are based on animal experiments using doses many times greater than any person would consume. But even some mainstream experts remain wary of artificial sweeteners, partly because of the lack of long-term studies in humans. In 2006, an Italian study generated some legitimate concern when it reported that aspartame increased the risk of cancer. Even though it was only an animal experiment, the study was large and involved fairly realistic doses of the sweetener.

Even if safety weren't an issue, artificial sweeteners might still be a problem because they may set people (especially children) up for bad eating habits by encouraging a craving for sweetness that makes eating a balanced diet difficult.

The counterarguments? Evidence that artificial sweeteners can help with weight control and loss, whatever the effects on the palate. And some experts see the safety concerns as overblown with little, if any, data from human studies to back them up.

One thing is clear: No one with the rare metabolic disorder phenylketonuria should use aspartame because it contains phenylalanine, which they can't metabolize.

|

Tips for cutting down your sweetener consumption

|

Sugar alcohols

The names of the sugar alcohols (sometimes called polyols) usually end in "–tol." Erythritol, isomalt, lactitol, maltitol, mannitol, polyglycitol (usually listed as HSH, for "hydrogenated starch hydrolysates"), sorbitol, and xylitol have been approved in the United States.

In sweetening power, the sugar alcohols are closer to sucrose and fructose than to the super-sweet artificial sweeteners, but they supply fewer calories than sucrose and the other sugars because they aren't completely absorbed in the digestive tract. They don't affect blood-sugar levels as much as sucrose, a real advantage for people with diabetes, and they don't contribute to tooth decay, so they're the main sweetener in most varieties of sugarless gum. Sugar alcohols are also used in candies, baked goods, ice creams, and fruit spreads. Read the ingredients carefully, and you'll spot them in toothpaste, mouthwash, breath mints, cough syrup, and throat lozenges. In foods, they're not as ubiquitous as sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, or for that matter, aspartame or sucralose — in part, because consuming too much (e.g., more than 50 grams per day of sorbitol or 20 grams per day of mannitol) can cause gas, bloating, and diarrhea. Whether they have more serious long-term effects at lower intakes isn't known.

Sweetened beverages

Sweeteners added to sports and juice drinks are particularly troubling because many people think those drinks are relatively healthful. Between 1977 and 2001, our energy intake from sweetened beverages more than doubled, according to University of North Carolina researchers. And studies have shown that people don't cut back on their overall calorie intake to offset the extra calories from such beverages.

Researchers are beginning to document the adverse health outcomes. Harvard researchers reported that women who drank one or more sugar-sweetened soft drinks per day were 83% more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than women who drank less than one a month. Not surprisingly, they were also more likely to gain weight.

When children regularly consume beverages that are sweetened — with artificial sweeteners, sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, or fruit-juice concentrate — they're getting used to a level of sweetness that could affect their habits for a lifetime. Diet surveys have found that American adolescents drink two 12-ounce sweetened soft drinks per day — the equivalent of 20 teaspoons of sugar and 300 calories.

One of the problems with sweetened beverages is that they are beverages — that is, watery. "Low-viscosity" high-calorie drinks may deceive us by preventing our bodies from "reading" calories, a capacity that depends, in part, on the thickness of a liquid (a milkshake has more calories than whole milk, and whole milk, more than skim).

A 2004 editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association said that reducing the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages "may be the best single opportunity to curb the obesity epidemic." And in March 2006, a Beverage Guidance Panel — which includes Dr. Walter Willett, chair of the nutrition department at the Harvard School of Public Health — issued its proposed "guidance system for beverage consumption."

The six-level system emphasizes beverages "with no or few calories" — especially water — over those with higher calorie content and recommends drinking no more than 8 fluid ounces of calorically sweetened sodas, juice drinks, or energy (or sports) drinks per day. Two months later, former President Bill Clinton and the American Heart Association brokered a deal with the soft-drink industry to remove most sweetened soft drinks from the public schools over a four-year period.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.